Old photographs of Americans who fought in the Revolution are quite rare. Few of the Patriots of 1775 to 1783 lived until the dawn of practical photography in the early 1840s. Moreover, the ravages of time have claimed the vast majority of portraits from the 1840s and 1850s.

According to PetaPixel, 81 years after the war, Rev. E. B. Hillard and two photographers embarked on a trip through New England in 1864 to visit and photograph the six known surviving veterans of the American Revolution. All of them American Patriots were over 100 years old. The glass plate photos were printed into a book titled The Last Men of the Revolution.

In 1976, journalist Joe Bauman stumbled upon Rev. E. B. Hillard’s photos. Realizing the rarity of the photos, Joe Bauman set out to find if there are more of them.

Bauman dug into their histories to see if they had been involved in the Revolution. In the end, the journalist spent 3 decades building what is now considered the biggest collection of daguerreotypes showing veterans of the Revolutionary War.

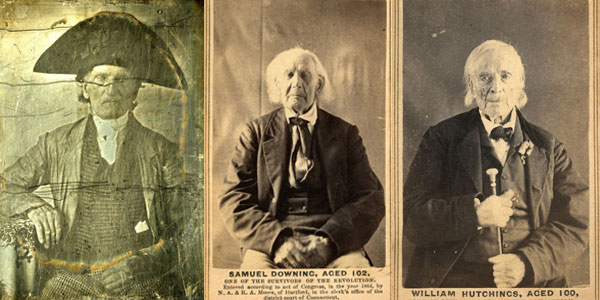

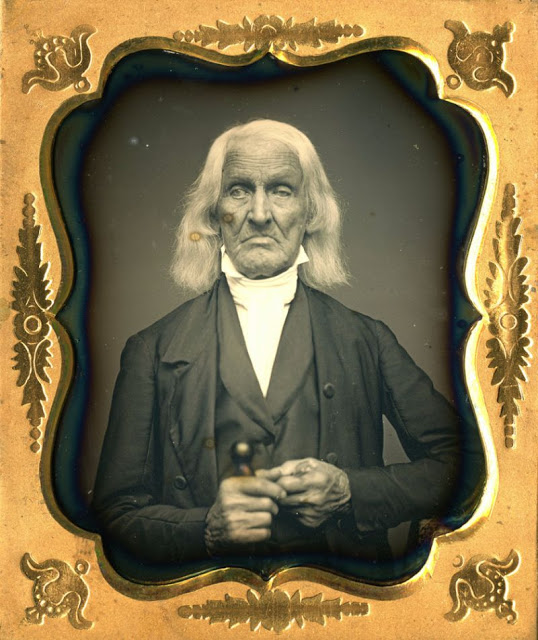

Peter Mackintosh was a 16-year-old blacksmith in Boston when a group of men rushed into the shop on the night of December 16, 1773 , grabbed ashes from the hearth and rubbed them on their faces. They were among those running to Griffin’s Wharf to throw tea into the harbor as part of the Boston Tea Party that started the Revolution. Mackintosh later served in the Continental Artillery, a craftsman attached to the army who shoed horses and repaired cannons, including one mortar whose repair Gen. George Washington oversaw personally. During his last years, Mackintosh and his lawyer fought for the pension he deserved. The government awarded it to his family only after his death, which was on November 23, 1846 at age 89.

Photo credit: Rev. E. B. Hillard | Courtesy of Joseph Bauman

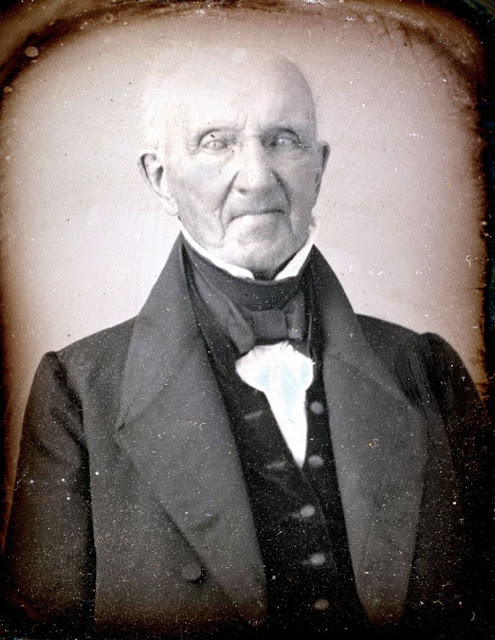

Simeon Hicks was a Minuteman from Rehoboth, Massachusetts who drilled every Saturday in the year leading up to the war. When he heard the alarm the day after the Battles of Lexington and Concord, the sparks that set off the Revolution, he immediately joined thousands of other New Englanders in sealing off the enemy garrison in Boston. He served several short enlistments and fought in the Battle of Bennington, August 16, 1777. After the war Hicks lived in Sunderland, Vermont as a celebrity. He was the last survivor of the Battle of Bennington.

Photo credit: Rev. E. B. Hillard | Courtesy of Joseph Bauman

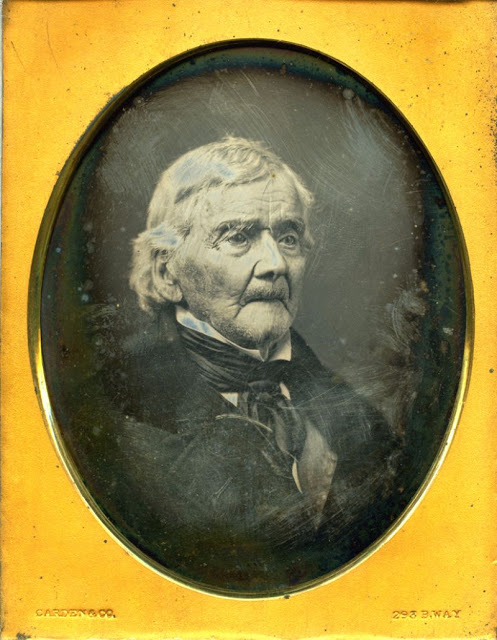

Jonathan Smith fought in the Battle of Long Island (1778). His unit was the first brigade that went out on Long Island, and was discharged in December after a violent snow storm. After the war he became a Baptist minister. He was married 3 times and had 11 children. The first two wives died and for some reason he left his third wife in Rhode Island to live with two of the children in Massachusetts. He died in 1855.

Photo credit: Rev. E. B. Hillard | Courtesy of Joseph Bauman

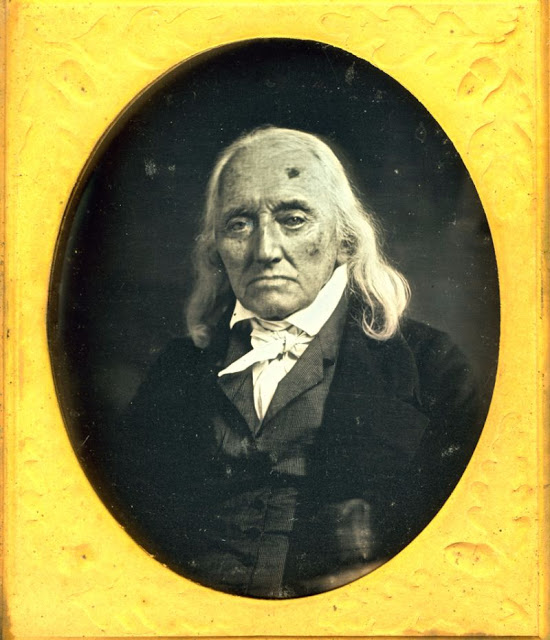

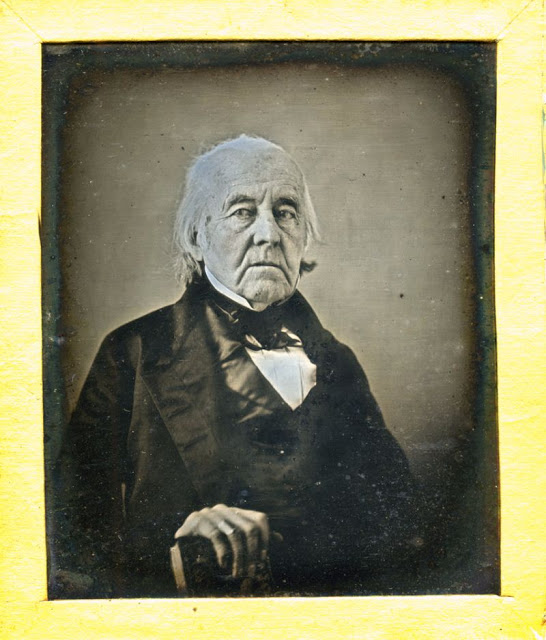

George Fishley was a soldier in the Continental army. When the British army evacuated Philadelphia and raced toward New York City, his unit participated in the Battle of Monmouth. Later he was part of the genocidal attack on Indians who had sided with the British, a march led by Gen. John Sullivan through “Indian country,” parts of New York and Pennsylvania. Fishley’s regiment, the Third New Hampshire, was in the midst of the campaign’s only contested battle. After the Battle of Chemung in 1779, the Americans had devastated 40 Indian towns and burned their crops. Later Fishley served on a privateer — a private ship licensed to prey on enemy shipping — and was captured by the British. Fishley was a famous character after the war in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, where he lived. He was known as “the last of our cocked hats” — Continental soldiers wore tall, wide, Napoleonic-looking headgear with cockades. He marched in parades wearing the hat, which his obituary said “almost vied in years with the wearer.”

Photo credit: Rev. E. B. Hillard | Courtesy of Joseph Bauman

James W. Head joined the Continental Navy at age 13 and served as a midshipman aboard the frigate Queen of France. When Charleston, South Carolina, came under attack, 5 frigates, including the Queen of France, and several merchant ships were sunk in a channel to prevent the king’s troops from approaching the city from one strategic direction. Head and other sailors fought as artillerymen in forts and were captured when the Americans surrendered — the Patriots’ biggest and arguably most disastrous surrender of the war. Taken as a prisoner of war, Head was released at Providence, Rhode Island and walked home. His brother wrote that when he arrived, Head was deaf in one ear and had hearing loss in the other from the cannons’ concussion. Settling in a remote section of Massachusetts that later became Maine, he was elected a delegate to the Massachusetts convention in Boston that was called to ratify the Constitution. When he died he was the richest man in Warren, Maine and stone deaf because of his war injuries.

Photo credit: Rev. E. B. Hillard | Courtesy of Joseph Bauman

Rev. Levi Hayes was a fifer in a Connecticut regiment that raced toward West Point to protect it from an impending attack. He also participated in a skirmish with enemy “Cow Boys” at the border of a lawless region called the Neutral Ground (most of Westchester County, New York, and the southwestern corner of Connecticut). In the early years of the 19th century, he helped organize a religiously-oriented land company that headed into the wilderness of what was then the West. They settled Granville, Ohio, where he was the township treasurer and a deacon of his church.

Photo credit: Rev. E. B. Hillard | Courtesy of Joseph Bauman

Daniel Spencer served as a member of the backup troops sent to cover the operatives in a secret mission to capture Benedict Arnold, after he had defected to the British. The maneuver failed when Arnold shifted his headquarters. A member of the elite Sheldon’s Dragoons, Spencer was in a few skirmishes. He sat up all night fanning his commanding officer, Capt. George Hurlbut, who had been shot in a fight during that the British captured a supply ship. Spencer’s account of the death of the officer differed markedly from that of Gen. Washington’s. Spencer said the wounds of the officer had nearly healed when he caught a disease from a prostitute and this illness killed him. Washington said he died of his wounds. Spencer’s pension was revoked soon after it was granted and for years he and his family lived in severe poverty. Eventually his pension was restored. He was the guest of honor during New York City’s celebration of July 4, 1853.

Photo credit: Rev. E. B. Hillard | Courtesy of Joseph Bauman

As a boy, Dr. Eneas Munson knew Nathan Hale, the heroic spy who was executed and said he regretted that he had only one life to give for his country. As a teenager, Munson helped care for the wounded of his hometown, New Haven, Connecticut, after the British invaded. He was commissioned as a surgeon’s mate when he was 16, shortly before he graduated from Yale. He extracted bullets from soldiers during battle. In 1781 he as part of Gen. Washington’s great sweep to Yorktown, Virginia, which led to Gen. John Burgoyne’s surrender and American victory of the Revolution. During the fighting at Yorktown he was an eyewitness to actions of Gen. Washington, Gen. Knox, and Col. Alexander Hamilton. Dr. Munson gave up medicine after the war and became a wealthy businessman, fielding trading ships, underwriting whalers and sealers, and venturing into real estate and banking. But throughout his life, his family spoke of how he loved recalling the exciting days of the war, when he was a teenage officer.

Photo credit: Rev. E. B. Hillard | Courtesy of Joseph Bauman

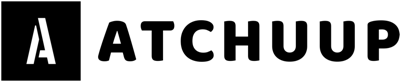

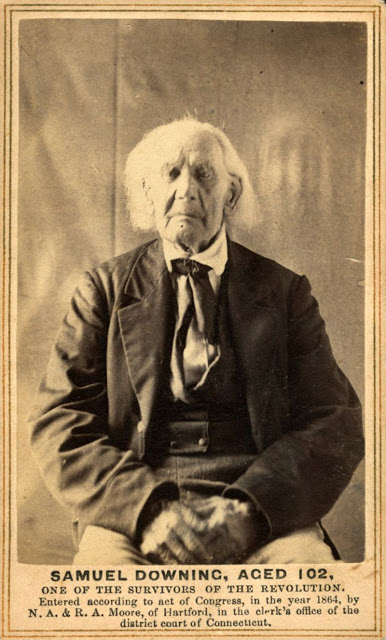

Samuel Downing enlisted at age 16, and served as a private from New Hampshire. At the time his picture was made, he was 102 and living in the town of Edinburgh, Saratoga Country, New York. He died in 1867.

Photo credit: Rev. E. B. Hillard | Courtesy of Joseph Bauman

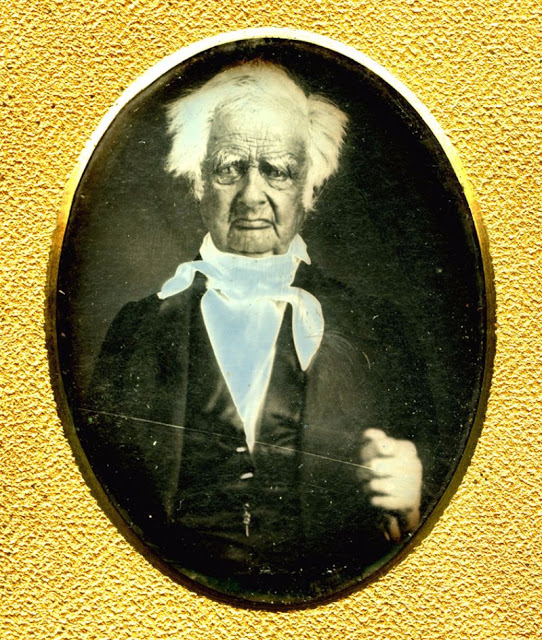

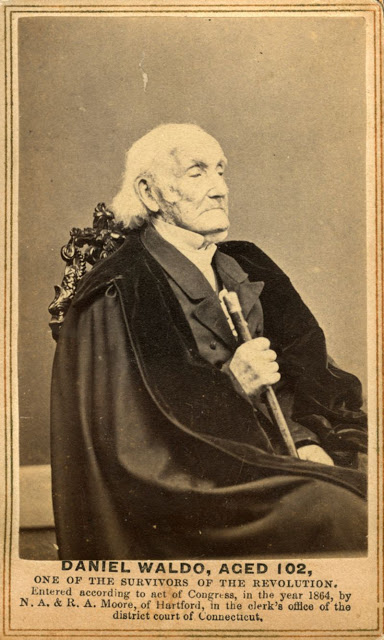

Rev. Daniel Waldo was drafted in 1778 for a month of service in New London. After that, he enlisted for an additional 8 months, and in March 1779 was taken prisoner by the British at Horseneck. After he was released, he returned to his home in Windham and took up work on his farm again.

Photo credit: Rev. E. B. Hillard | Courtesy of Joseph Bauman

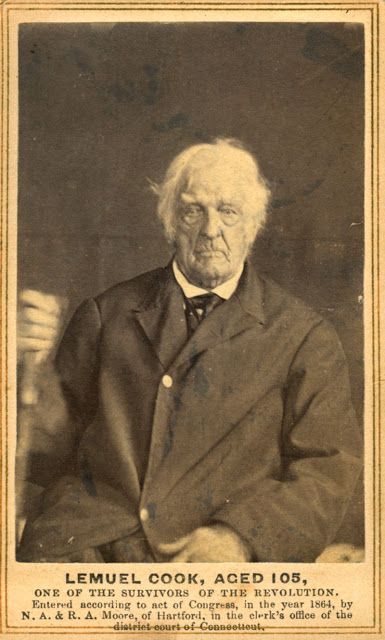

Lemuel Cook witnessed the British surrender at Yorktown, the event that guaranteed American independence. He said, “Washington ordered that there should be no laughing at the British; said it was bad enough to surrender without being insulted. The army came out with guns clubbed on their backs. They were paraded on a great smooth lot, and there they stacked their arms.”

Photo credit: Rev. E. B. Hillard | Courtesy of Joseph Bauman

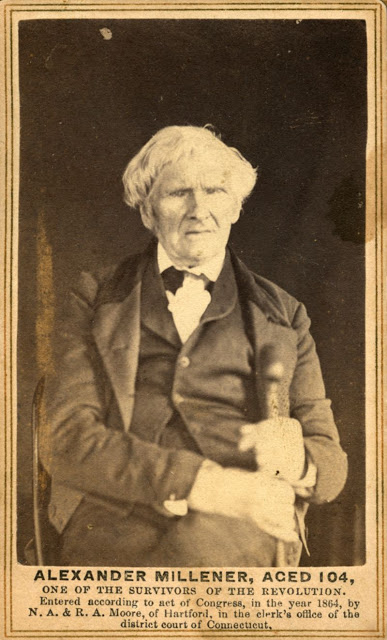

Alexander Milliner enlisted as a drummer boy who served in Gen. Washington’s Life Guard unit. He was a favorite of Washington’s, often playing at his personal request. Milliner was at the British surrender at Yorktown, about which he said, “The British soldiers looked down-hearted. When the order came to ‘ground arms,’ one of them exclaimed, with an oath, ‘You are not going to have my gun!’ and threw it violently on the ground, and smashed it.”

Photo credit: Rev. E. B. Hillard | Courtesy of Joseph Bauman

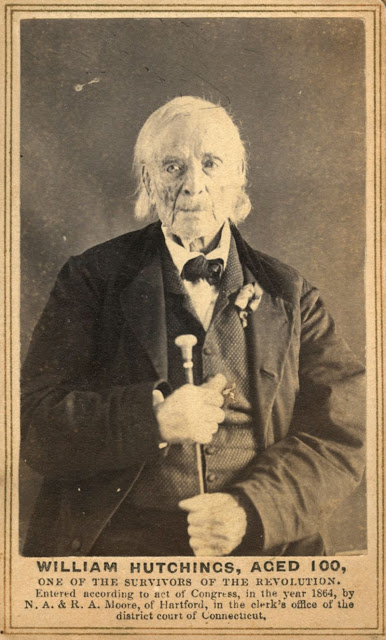

William Hutchings enlisted at age 15 for the coastal defense of his home state, New York. Writes Hillard in The Last Men of the Revolution, “The only fighting which he saw was the siege of Castine, where he was taken prisoner; but the British, declaring it a shame to hold as prisoner one so young, promptly released him.”

Photo credit: Rev. E. B. Hillard | Courtesy of Joseph Bauman